Portal, AZ - Rodeo, NM

Serving The Communities Of Portal and Rodeo (www.portal-rodeo.com)

Serving The Communities Of Portal and Rodeo (www.portal-rodeo.com)

Kiss Of Death

The Kiss Of Death

Kissing Bugs In The Bedroom

by Dr. Howard Topoff

In The Beginning!

It was about 2:00 am that I woke up, scratching my scalp. Within minutes, my entire body was itching uncontrollably. My heart was pounding, and my mouth swollen. My commotion woke up Carol and I asked her if we had bed bugs. A look in the bathroom mirror scared me as a rash had broken out. We got out of bed and shook the blanket. And there it was, falling to the floor, a bloated kissing bug. Bloated with MY blood. I downed a half bottle of Benadryl and the itching subsided, but I don’t think I fell back to sleep that night. The next day, I made an appointment with Dr. Jacob Pinnas, an allergist in Tucson who specialized in kissing bug bites. He told me that many people have an extraordinary sensitivity to kissing bug bites and he had more patients die from kissing bug bites than all the bee and wasp stings combined. And like bee keepers, some people become resistant to kissing bug bites with each exposure. But others, unfortunately, become more sensitive with successive bites and become susceptible to anaphylaxis. This is a bug to take seriously, so please read on!

What are kissing bugs?

They are hematophagous (blood-sucking) insects. They are true bugs, in the insect order Hemiptera. The family name is Reduviidae. They are also called cone-nose bugs, assassin bugs, and vampire bugs. In some countries of South America, inhabitants have historically battled a bloodsucking insect called vinchuca. Charles Darwin, who often slept on the ground in South American forests, reported being bitten many times by these kissing vinchucas. One hypothesis about the origin of Darwin’s poor health for the remainder of his life is that he contracted Chagas disease from the bugs. But, it’s just a hypothesis.

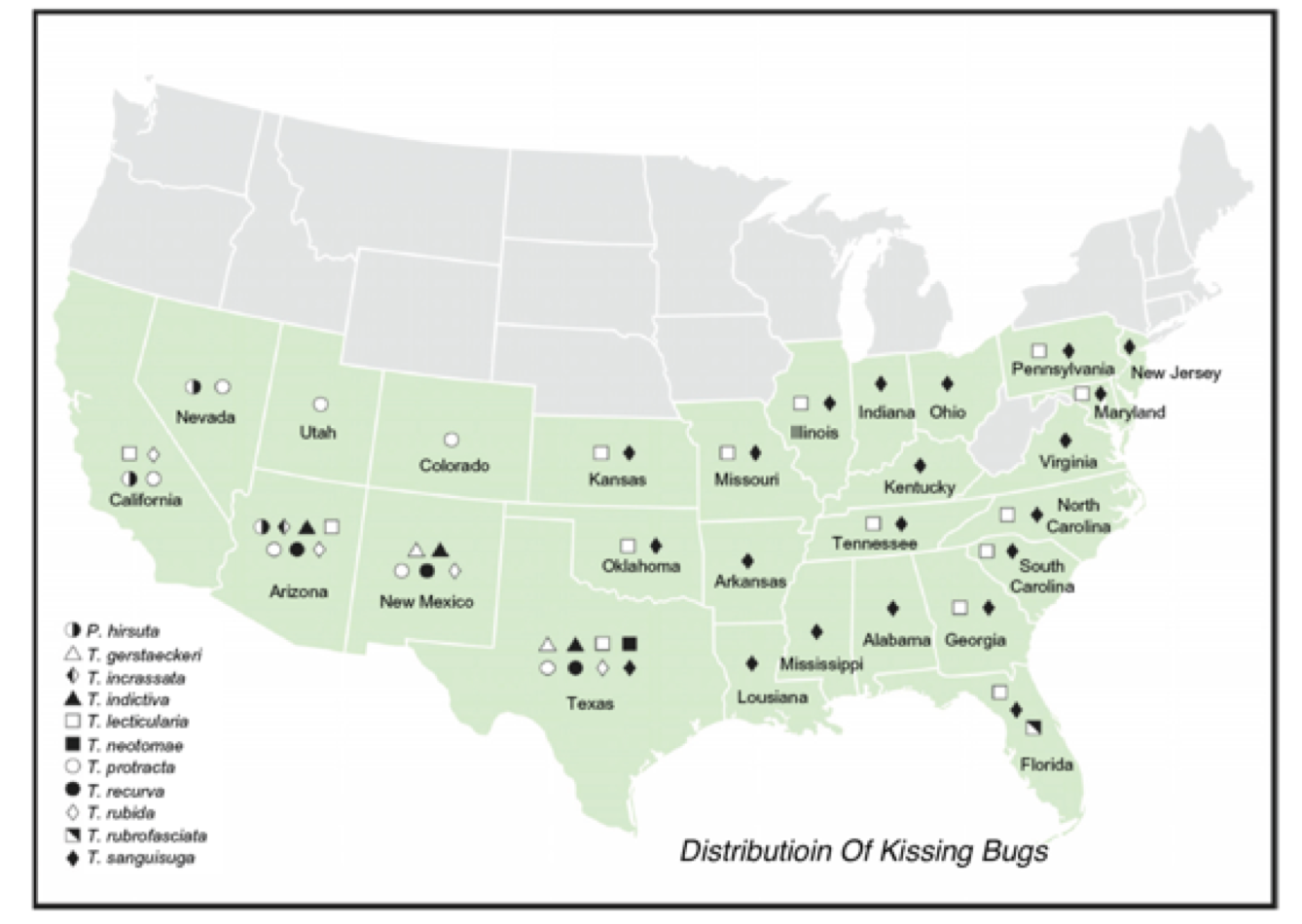

How many species of kissing bugs are there?

A lot! Approximately 130 species, all in the New World, with 11 species in the United States. The most common species in our area is Triatoma rubida. Here is a photo of the bug. Note the long “snout,” and the black rectangles embedded in an orange background on the abdomen.

Triatoma rubida

People often mistake another bug for a kissing bug. This is the leaf-footed bug, also called cactus bug (genus Leptoglossus) that is very common, and found in many homes. Note (in the photo below) the dilation on each rear leg (tibia). Although also a true bug, it belongs to a different family - Coreidae. In some areas it is an agricultural pest, but completely harmless to people.

Leptoglossus

Where do kissing bugs live?

Kissing bugs in Arizona, particularly Triatoma rubida and Triatoma protracta, commonly infest packrat nests. But, they can also live:

• Beneath porches

• Between rocky structures

• Under cement

• In rock, wood, brush piles, or beneath bark

• In other animal burrows

• In outdoor dog houses or kennels

• In chicken coops or houses

In areas of Latin America where human Chagas disease is an important public health problem, the bugs nest in cracks and holes of substandard housing.

Are they seasonal?

We have (very) occasionally seen them during any month, even January. But they do have seasonal peaks of activity.

Before or during the summer monsoon rains they engage in dispersal (and mating) flights at dusk. Like many nocturnal insects, they are attracted to lights in houses. Dispersal flights can be up to one mile, so you don’t have to have pack rat nests near your home. With increasing urbanization, and the accompanying reduction in rodent populations, kissing bugs become even more reliant on humans for blood meals.

Once inside your house, what attracts them to YOU?

Kissing bugs have an extraordinary sensitivity to carbon dioxide, lactic acid, and several fatty acids, all excreted by people. They also detect infrared radiation (HEAT), enabling them to find you in any room.

If the bugs are in your house during daylight, they typically hide in a variety of crevices (furniture, mattresses, pillow cases, you name it).

Why are they called kissing bugs?

It is a very appropriate name for an insect that frequently bites people on the lips. The skin on our lips is very thin compared with other parts of the face, and the red color indicates that the copious blood supply is not far from the surface. But the bug is perfectly content to penetrate other parts of the face. After all, since our face is usually out in the open while we are sleeping, it’s the path of least resistance. Nevertheless, kissing bugs can “nail” you anywhere on the body. They do not bite through bed sheets or blankets.

What is the bite like?

Once a host is located, a hungry bug extends its proboscis and inserts it into the skin of the host. Small, serrated mandibles are then used to cut the epidermis. Finally, a sharp stylet is inserted though the mouthpiece to search for capillaries. Sometimes, the host detects the minor sensation caused by a kissing bug’s probing and moves or shifts position. A bug can take in more blood than its own weight, so feeding may last 1 - 20 minutes.

Why don’t we feel the bite?

We all have countless touch receptors on just about every part of our body, and many people do awaken to the stimulus of a kissing bug crawling on their skin. Experiments have shown, however, that the bite is essentially painless. This explains why most patients presenting to emergency rooms with anaphylaxis due to kissing bug bites are rarely aware of a bite preceding anaphylaxis – they awaken at night with intense itching over the body and difficulty breathing. If they don’t see the bug, they may attribute it to a spider (which CAN cause similar symptoms).

Chemicals in kissing bug saliva are able to inhibit voltage-gated sodium channels. Without getting technical, these channels allow many nerve cells (including pain receptors) to “fire,” sending signals to the brain. This chemical inhibition may account for the bug’s anesthetic effect.

Do both males and females feed on blood?

Yes. Unlike mosquitoes, in which females feed on blood and males drink nectar, both sexes of kissing bugs suck blood. And so do all 5 immature stages. Kissing bugs probably evolved from insects that fed on insect hemolymph (blood) and then changed to specialize on vertebrate blood.

What are the symptoms of a kissing bug bite?

The good news is that, for many people, a bite from a kissing bug is not much different than a mosquito bite. Itching, but no severe symptoms. But for some people, get ready for a LONG list!

A major salivary chemical (antigen) in kissing bugs is called procalin, which can cause severe allergic reactions in humans. Other enzymes in the saliva prevent platelets from aggregating, thus maintaining an adequate flow of blood from the capillaries. Common symptoms include:

Hives

Nausea - Vomiting

Severe itching (locally, or entire body)

Constriction of the throat

The Romañia sign (swelling of the eyes)

Swelling of the tongue and throat

Difficulty swallowing, speaking, breathing

Dangerous drop in blood pressure (shock)

What is the treatment for a kissing bug bite?

For mild symptoms such as itching, an over the counter antihistamine medication like Benadryl should be sufficient.

But note that the more severe symptoms listed above are indications of ANAPHYLAXIS, a severe allergic reaction that needs to be treated right away. If you have an anaphylactic reaction, you need an epinephrine (adrenaline) shot as soon as possible, and someone should call 911 for emergency medical help. Left untreated, it can be deadly. Keep an EpiPen in your medicine chest, and make sure it has not expired. They used to be extremely expensive ($300), but CVS now sells a generic version - a 2-pack for about $100.00. Get a prescription from your health care provider and GET IT! It could save your life.

Is it easy to find the bug in my bed?

After a blood meal, the bug is swollen and quite lethargic. Indeed, it can barely move. Shake out your blankets, pillow cases, and sheets, and the bug should fall onto the floor.

What’s the life cycle?

Kissing bug eggs hatch into wingless nymphs, of which there are five stages, each stage requiring at least one blood meal to molt. The fifth immature stage molts to a winged adult that, when given the opportunity, feeds every several weeks, or even more than once a week, depending upon ambient temperature and season of the year.

Are humans the only species bitten?

Nope. They bite a large variety of animals, including dogs and other mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, and even some invertebrates. Kissing bugs can be a serious pest on dogs. Bravecto (and similar products) is a flea-and-tick-killing medication that provides dogs with protection. The active ingredient in the medication is fluralaner, which is a systemic ectoparasiticide (meaning that it kills bugs that live on the outside of your dog’s body). There is some evidence that it will also kill kissing bugs, but I have not seen a published study.

How can I keep kissing bugs out of my house?

Short answer: it ain’t easy!

Synthetic pyrethroid sprays have been used successfully in Latin America to eliminate house infestations. The fact that, in our neck of the woods, bugs are found indoors only occasionally, suggests they are NOT living (and breeding) inside our homes. Accordingly, chemical sprays and professional pest control operators are unnecessary (and unhealthy).

Note that roach hotels or other "bait" formulations do not work against kissing bugs.

Precautions to prevent house infestation include:

• Sealing cracks and gaps around windows, walls, roofs, and doors

• Removing wood, brush, and rock piles near your house

• Using screens on doors and windows and repairing any holes or tears

• If possible, making sure yard lights are not close to your house (lights attract the bugs)

• Sealing holes and cracks leading to the attic, crawl spaces below the house, and to the outside

• Having pets sleep indoors, especially at night

• Keeping your house and any outdoor pet resting areas clean, in addition to periodically checking both areas for the presence of bugs

. Remove pack rat nests from around your house. I have found 2-18 kissing bugs living in a single packrat nest.

How can I keep kissing bugs off of me?

As long as you live and breathe, kissing bugs can find you. Several people in Portal, who know from experience that they are sensitive to kissing bug bites, sleep under a ceiling-to-floor bed net. They are inexpensive $10.00 - $75.00 and come in several styles. If you have 4 posts at the corners of your bed, some models attach to the poles. Otherwise, you can purchase a net that attaches to the ceiling (with a hook) over the center of the bed, and drapes down. Make sure you get one large enough to tuck under all sides of the mattress. Using the net during the months of May-July should offer sufficient protection. This what Carol and I sleep under during these months.

What is Chagas disease?

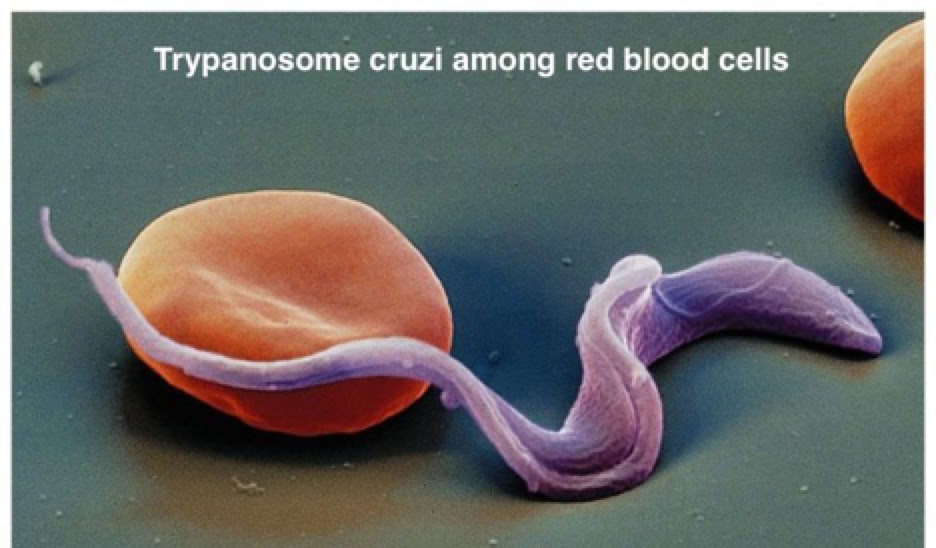

Chagas disease (named after the Brazilian physician Carlos Chagas), is caused by the protozoan parasite Trypanosoma cruzi (see photo below), which is transmitted to animals and people by kissing bugs and is found only in the Americas (mainly, in rural areas of Latin America where poverty is widespread).

Chagas disease has an acute and a chronic phase. If untreated, infection is lifelong.

Acute Chagas disease occurs immediately after infection, may last up to a few weeks or months, and parasites may be found in the circulating blood. Infection may be mild or asymptomatic. When signs and symptoms do occur, they are usually mild and may include:

• Swelling at the infection site

• Fever

• Fatigue

• Rash

• Body aches

• Eyelid swelling

• Headache

• Loss of appetite

• Nausea, diarrhea or vomiting

• Swollen glands

• Enlargement of your liver or spleen

A particularly interesting symptom of the acute phase is called the Romañia sign, a preorbital swelling of the eye (see photo below). The Romañia swelling can also be present without being infected, as part of the allergic reaction following a bite near the eye,

The Romaña Sign

Following the acute phase, most infected people enter into a prolonged asymptomatic form of disease, during which few or no parasites are found in the blood. During this time, most people are unaware of their infection. Many people may remain asymptomatic for life and never develop Chagas-related symptoms. However, an estimated 20 - 30% of infected people will develop debilitating and sometimes life-threatening medical problems over the course of their lives.

Complications of chronic Chagas disease may include:

• heart rhythm abnormalities that can cause sudden death;

• a dilated heart that doesn’t pump blood well;

• a dilated esophagus or colon, leading to difficulties with eating or passing stool.

How does the kissing bug spread the parasite that causes Chagas disease?

The insect vector transmits the parasite to hosts by biting and subsequently defecating near the site of the bite. The parasites live in the digestive tract of the bugs and are shed in the bug feces. When infectious bug fecal material contaminates the site of the bug bite on a mammal, transmission of the parasite can occur. So far, at least 8 species can transmit the trypanosome.

While transmission of T. cruzi by kissing bug bites is the most common form of disease acquisition, Chagas disease can be acquired congenitally, through blood transfusion, organ transplantation, and ingestion of contaminated food or drink.

Many species of animals upon which kissing bugs feed can serve as a source of parasite infection to the bug, and the Trypanosoma cruzi parasite has been found to infect domestic dogs, humans, opossums, wood rats armadillos, coyotes, mice, raccoons, skunks, and foxes. Wildlife are responsible for maintaining this parasite in nature. Therefore, Chagas disease emerges at the intersection of wildlife, domestic animals, humans, and vector populations.

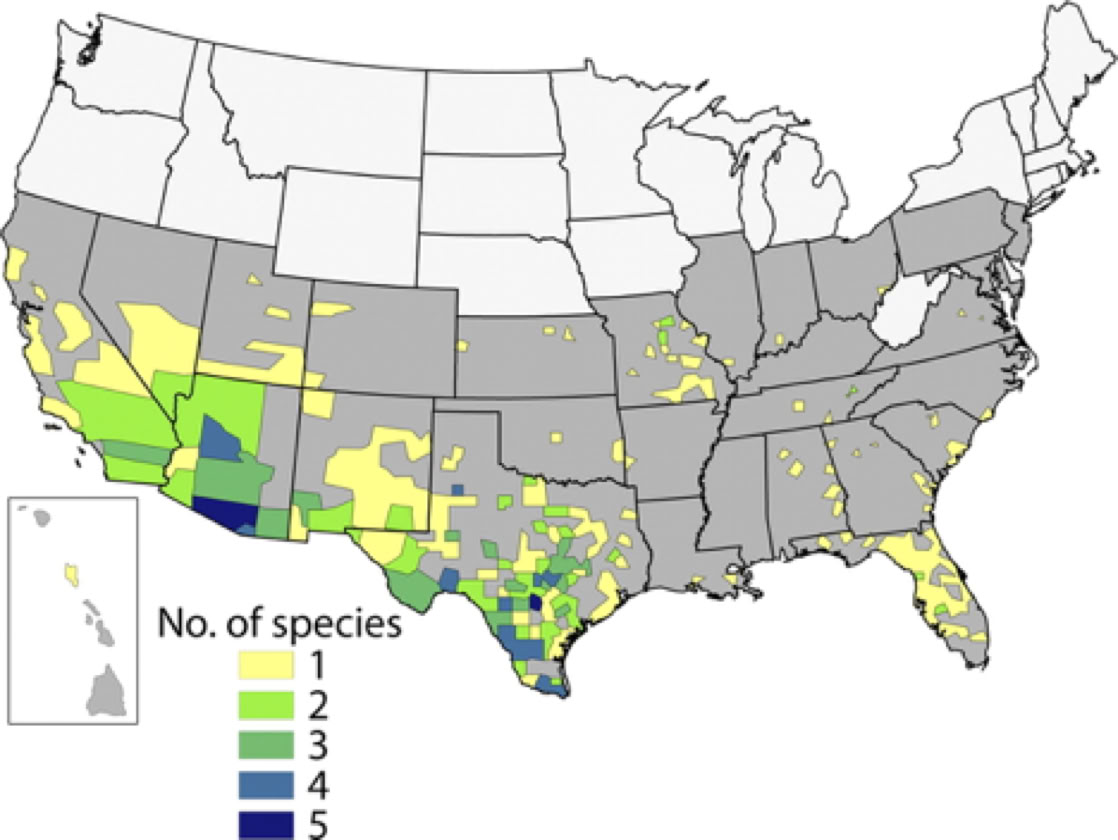

Since T. cruzi is transmitted to humans through the feces of the bugs, the delayed defecation and movement away from the host are likely one reason transmission of Chagas disease from these species is less likely than from South American kissing bugs. However, a recent report has found that kissing bugs CAN bite and defecate at nearly the same time, so it is now believed that Chagas Disease can be transmitted locally, and that several cases of this autochthonous (meaning local) infection have been reported in Arizona. The lesson here is that we need to be extra cautious - keep lights off in the bedroom, check sheets, pillowcases and mattresses, and pay extra attention to the health status of your pets.

What is the status of Chagas Disease in The United States?

An estimated 5.7 million people are infected with Chagas disease worldwide. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimates that approximately 300,000 people are living with this disease in the United States. Roughly 30% of those infected will develop serious cardiac, digestive, or neurological disorders. Most are immigrants from Latin America, have Chagas Disease in its chronic phase, and can therefore transmit the parasite to kissing bugs.

The most recent epidemiological investigation to back up the CDC estimate was a study of almost 5,000 Latin American-born residents of Los Angeles County. It found that 1.24% tested positive for Chagas disease.

So far few individuals have contracted the disease from bites in The United States. This may be due to a behavioral difference between the bug species here and in Latin America. The species here usually don't defecate while they are feeding. This delay prevents the trypanosome from being rubbed into the wound created by the bite. But a recent report stated that some bugs DO defecate while feeding and local cases of infestation have been reported in many southern and western states, including Arizona. There is currently no vaccine for Chagas Disease.

Do trypanosomes cause any other human diseases?

In Africa, a different species of the protozoan transmits sleeping sickness, via the bite of the tsetse fly.

Does Chagas Disease affect dogs?

In dogs, infection with the Chagas parasite can cause severe heart disease, however many infected dogs may remain asymptomatic. The degree of complications relate to the dog’s age, activity level, and the genetic strain of the parasite. Testing for canine Chagas disease is by means of a blood test. Unfortunately, treatment options are not readily available, although some research teams are developing new treatment approaches that are promising. There is currently no vaccination that protects against Chagas disease for either dogs or humans.

Why are dogs at risk of being infected?

High densities of dogs in confined areas are associated with heat and carbon dioxide that attract kissing bugs that seek blood meals. Furthermore, dogs may easily consume kissing bugs in kennels. Because adult bugs fly towards lights, keep kennel areas dark after sunset. Some insecticides are effective against kissing bugs when sprayed around the kennel area.

Can we get Chagas Disease from other mammals?

Good question!

In the United States, at least 24 mammal species have been documented as hosts of Trypanosome cruzi. Evidence suggests that all mammals may be considered as susceptible to infection. What if an infected, and rabid, dog, fox, skunk, etc. bites a human? This is a great question but it has never been studied. Could be a great Ph.D. thesis project.

Kissing Bug Stories

This “Kiss Of Death” web page is a work in progress, and I intend to update it as new studies are published. An interesting feature will be posting your experiences with kissing bugs, so please do send me some juicy stories.

July 13, 2013 - by H. Topoff

My Animal Behavior Class excavated a pack rat nest near my home. First we erected a mosquito tent over the nest, to capture any insects attempting to fly away. By the end of the excavation, we had extracted 18 kissing bugs from that single nest! Pity the poor rat.

May 29, 2017 - by H. Topoff

Carol did a wash two days ago and piled my clean clothes on the dresser near our bed. After a jog an hour ago, I showered and attempted to dress. As I was putting on a clean pair of underwear from the pile, this kissing bug fell from inside the shorts to the floor. This is shaping up to be a bad year for kissing bugs. Maybe we'll have dinner tonight inside our bed net!

May 31, 2017 - by Mark & Diana Jankowski

About 10 years ago we spent a couple of nights at the blue cottage, just off Portal Road, and were invaded by a swarm of these reduviids. They were landing on any area of exposed skin, especially on our face and head. We were able to isolate ourselves from the horde of assailants by remaining inside the cottage and methodically destroying every individual we could find. Yes, they do hide under beds and behind curtains! To the best of our knowledge we were not bitten, but the enemy suffered heavy losses.

May 31, 2017 - by Bill Cavaliere

Every time I get bitten by a kissing bug, the reaction gets worse. Early bites were extreme itching confined to the area of the bite. Then the areas would get progressively larger.

One night I woke suddenly to find my entire body swollen from head-to-toe, itching all over like I had never experienced before. We found a kissing bug on the bed and shook it onto the floor. When my wife stepped on it, it spurted blood. Then my lips started to get numb and I had difficulty swallowing. Every inch of skin on my body itched terribly. My wife gave me a Benadryl and after a while the itching subsided a little and the swelling went down.

May 31, 2017 - by Delane Blondeau

A couple of early evenings ago I was bitten by a kissing bug. The spot turned red and itched like crazy. I thought the stick you can buy for bug bites has alcohol in it, I think, so I took a pad of toilet paper and soaked it with rubbing alcohol and placed it on the spot for maybe 2 minutes. The red remained, but the itching stopped and did not come back – even in a warm shower. The red is fading away. When I pulled the sheets off the bed on laundry day, there was a fat kissing bug that came up from between the mattress and the headboard with the sheet. Aha, a RESIDENT (about 4 days after my bite.) He was fat with my blood (I think she ). But now departed this life!

In my underwear!

Distribution Of Species Most Common In Portal-Rodeo

Distribution Of The 11 Kissing Bug Species In The United States

Occurrence Of Chagas Disease In The United States

(Colors Denote Number Of Kissing Bug Species)

A Thing Of Beauty Is A Joy Forever