Portal, AZ - Rodeo, NM

Serving The Communities Of Portal and Rodeo (www.portal-rodeo.com)

Serving The Communities Of Portal and Rodeo (www.portal-rodeo.com)

Biology Of Slave Making Ants

Invasion Of The Booty Snatchers

An Introduction To The Behavior of The Slave-Making Ant Polyergus topoffi

In 1865, the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States was ratified, abolishing slavery in America, but the ant world took little notice. Slavery among ants may be one of the most unusual forms of social behavior to have evolved, but workers of the species Polyergus topoffi - which are all female - live exclusively on slave labor and would die without workers of Formica to take care of them. That's what brings me to the Chiricahua Mountains of southeastern Arizona, where each afternoon I wait for an ant to emerge from her subterranean nest. That's right, I'm waiting for one ant, but she's no ordinary creature. The colony's survival depends on this single ant- called a scout - who has one Herculean mission: emerge from her nest, travel up to 150 yards, search under rocks and leaf litter for a disguised subterranean nest of the ant species Formica gnava, find her way home, and then lead about 2,000 pumped-up Polyergus workers on a slave raid back to the Formica nest. A slave raid?

The workers of Polyergus have lost the ability to forage for food, feed their brood or queen, or even clean their own nest. To compensate for these deficits, Polyergus has become specialized at obtaining workers from the related genus Formica to do these chores for them. This is accomplished by a slave raid, in which Polyergus penetrate a Formica nest, and capture the resident's pupal brood.

Back at the Polyergus nest, the raided brood is reared through development, and the emerging Formica workers then assume all responsibility for maintaining the permanent, mixed-species nest. They forage for food and regurgitate it to colony members of both species.

Of all behavioral adaptations necessary for the evolution of social parasitism, I have focused on the bizarre way in which Polyergus queens establish new colonies. To clarify this point, consider the straightforward process of colony founding by queens of free-living ants. After a mating flight, an inseminated female excavates a chamber, lays a few eggs, and nourishes her larvae with stored nutrients. When the first brood matures into adult ants, these workers feed the queen and the larvae of her subsequent broods. But this sequence simply will not work for a parasitic ant such as Polyergus, because she is, after all, a parasite: she can't feed herself, much less rear her own larvae. Her only recourse is to invade a Formica colony, kill the host queen, and somehow get the workers to accept her as their queen. If successful, these resident Formica workers will rear the brood of the Polyergus queen until her worker population is sufficiently large to supplement the slave force by staging raids on other Formica colonies.

Because colonies of Formica and newly-mated Polyergus queens are are very easy to collect, I was able to make detailed observations in laboratory nests of the takeover process. Within seconds after being placed inside a Formica nest, the Polyergus queen bolts for the Formica queen, literally pushing aside any Formica workers that attempted to grab her. The Polyergus queen's two main defensive adaptations are powerful mandibles for biting her attackers, and a repellant chemical (pheromone) secreted from the Dufour's gland in her abdomen. With the worker opposition liquidated, the Polyergus queen seizes and kills the Formica queen. Immediately after the death of the host queen, the Formica nest undergoes a most remarkable transformation. The Formica workers approach the Polyergus queen, and start grooming her. The Polyergus queen, in turn, assembles any scattered Formica pupae into a neat pile, and "triumphantly" stands on top of it. At this point, colony takeover is complete!

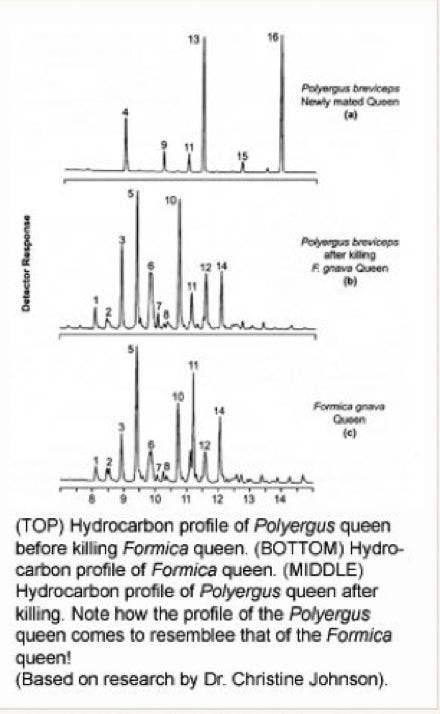

It occurred to me that this abrupt appropriation of the colony could be accomplished by what I call a "chemical heist." Accordingly, the Polyergus queen would acquire Formica queen chemicals during the very act of killing and licking her. To test this idea, I repeated the study, but with an interesting twist: to each laboratory nest, I added a dead Formica queen that had been frozen for 5 minutes, and then defrosted. The results were exactly as I had predicted. Upon entering the nest, the Polyergus queen ran past the attacking workers, pounced on the motionless Formica queen, and proceeded to bite and lick her just as if she were alive. And after about 30 minutes of working over the dead Formica queen, the Polyergus queen was again promptly groomed by the Formica workers and permanently accepted as their new queen. Recently, one of my students, Christine Johnson, demonstrated that during the act of Formica queen killing, the Polyergus queen does indeed incorporate a veritable cocktail of chemicals from the vanquished female.

A common question is why don't the Formica slaves run away, perhaps back to their own nest. The answer is that these ants are not enslaved in the human sense. Indeed, it's more like adopting a baby. Because they are snatched as pupae and reared in a Polyergus colony, the Formica workers become imprinted with the odors of the host ants. In a subterranean world where vision is virtually useless, a family - even one composed of different species - is defined by an arsenal of chemicals secreted by the ants and applied to all nest mates. In ants, the family that sprays together stays together!

Formica Queen Escapes During Slave Raid

Polyergus Worker carries stolen Formica pupa

Formica (Upside Down) Feeds Polyergus

Polyergus Queen Kills Formica Queen & Usurps Colony

Hydrocarbon Profile Of Polyergus Queen